MOUNT CAMEROON RACES FACTS AND FIGURES

The Mount Cameroon Race of Hope - facts and figures (Part 1)

By Simon Lyonga la Molombe

Pictures by Maths Anonymous

The 2025 edition of the mount Cameroon race of hope is already in view with the 22nd of February set aside for this great sports event on the calendar of local and international athletics. Another edition for the best talents to flex muscles as they tame the highest mountain in West and Central Africa, the second highest in Africa after the Kilimanjaro mountain range.

Far from being just another race to fulfill a calendar demand, this competition has gained in notoriety, bringing together some of the world’s finest mountain athletes. Over the years the race has won the heart of the nation being one of the few televised road and mountain races on the continent, but also an event that is considered by the population of the host town as a cultural jamboree, being on a mountain whose place in their everyday life is considered sacrosanct.

Enough reason for a track cleansing exercise on the eve of every race, conducted by the traditional rulers of Buea sub division as a vector to prevent calamity when the athletes climb up and down the rough, difficult and rugged mountain slopes.

In the meantime, the memories of the past editions of the race are still present in the minds of many, its evolution a source of pride to the people and the past winners elevated to special places in the minds of many for the pride they brought to their communities.

History holds that the Mount Cameroon race started in 1973, with the evolution of the race course going from the former tourism office in the station neighbourhood passing through the legendary Buea town green stadium to the present site, the molyko stadium. The change from the Buea town stadium to the present take off point having met with stiff opposition, seen as a slap in the face of the local population after their lead athlete the late Ngou Njombe David was accused of cheating on the race course. With no evidence to buttress the allegations from the organisers, the silver finish of the 1974 champion left a bitter taste in the mouths of many, not only because the locals wanted a win, but because its backslash caused them lose their preferred take-off point, from their mythical arena in the heart of their fief to an open space where they had no control.

In the meantime the evolution came along with new faces on the score sheet with a change in ambitions. From 1973 when the late John Ekema won, passing through the 1974 victory of the legend David Ngou Njombe to that of Amos Ndumbe Evambe in 1975, victory was more of winning a cultural event, mostly within a people who saw such as a show of tribal chauvinism and local challenge amongst villages than a will to make life earnings that were at a record low. A few crates of beer from the top sponsors, plus an envelope below three figures was shunned for the pleasure of seeing the winner come from one’s area of origin.

But this was fast discarded when in 1976, the Italian born clergy Fr Walters Stifter was on the starting bloc. Though his status was never seen as a threat, his win stunned many and was clearly the talk of the day. He became the man to beat, but the challenge failed as he won three successive editions.

Unverified Stories have been told of the mystical fights he had on the slopes in a bid to challenge his authority as the best athlete. Guinness did not organise a mountain race in 1979, 1980 and 1981 and when Guinness re-started the race in 1982, Fr Stifter did not participate as he had decided to retire from mountain races. He retired from the competition after his third win, supposedly an inner wish not to re-live the horror moments in his third attempt, but with a challenge on his successors. He dared them to win three successive editions like he did. And the late cleric never lived to see any, because since then no male athlete has succeeded with a triple consecutive win.

The first to try after him was the 1982 winner Simon Ndive Yonde from Bonakanda, buea, but after that triumph he was fast overtaken by events. Same for Gobina Franz Monyonge from Wondongo village who succeeded in 1983. Just when many thought it was a forgotten issue, the 1984 edition saw the coming of the then British mountain champion Mike Short. Mike Short won the race in 4hours6minutes, beating Fr Stifter’s record of 4hours19minutes. Mike Short won again in 1985, breaking his own record, with Timothy Lekunze coming second.

Mike Short returned to Cameroon again in 1986, setting the stage for a one in a lifetime competition with an indelible mark. He came to Cameroon to a rock star reception, his name was on every lip and his pre-competition Interviews expressed a confident runner whose ambition was to win a new crown of the competition, that of being termed the king of the mountain.

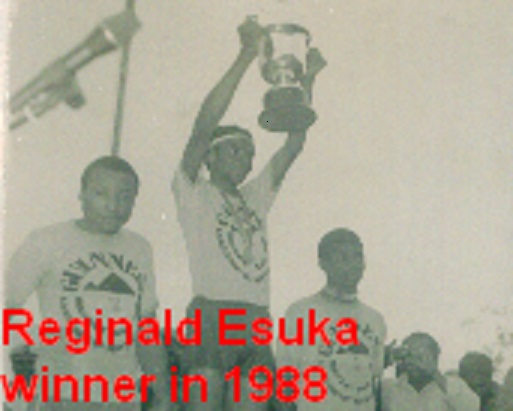

Far from the eyes of the camera, the Cameroonian chasing bunch never took that lying low, and the race day was a different story. Mike Short was beaten and a new name emerged; that of Lekunze Leku Timothy who at the time was training as a high school teacher at ENS Bambili, Bamenda. His victory made him a household figure in Cameroon, and was followed by another win in 1987. The increased interest and zeal that surrounded the 1986 edition came back in full force, as the boy from Labialem who now flew the flag of the Cameroon defence forces became a potential mountain king. In 1988, Mike Short brought his fellow country-man Jack Maitland to prevent Lekunze from winning the race the third time. Jack Maitland ascended the mountain so fast that he beat Mike Short’ ascent record by six minutes. Timothy Lekunze arrived the summit in second place, 14 minutes behind Jack Maitland. Everybody thought that Maitland would definitely win the race as he was leading Lekunze on the descent by a wide margin. What people did not know was that Lekunze was descending at a tremendous speed and at the same time, Maitland was very tired and hence was too slow on the descent. Lekunze overtook Maitland somewhere between hut 1 and Upper Farms. But, about 2 minutes after Lekunze overtook Maitland, he (Lekunze) developed blisters on the soles of his feet and couldn’t continue with the race. Reginald Esuka, native of Bakweri in Buea, eventually won the race. The 1989 race was the most controversial in the history of the Mount Cameroon race. David Ngou Njombe, former winner of the mountain race, was alleged to have cheated by hiding between Upper Farms and Hut 1 very early on the morning of the race, such that when the rest of the athletes took off from the Buea town stadium, he took off from his hiding place and arrived hut one 23 minutes inside Mike Short’s record of 43 minutes from the stadium to hut 1. Njombe was leading the race and was later overtaken on the descent by Jack Maitland, near the Presbyterian Youth Centre in Buea Town and went on to win the race. Guinness officials had disqualified Njombe, but, because Njombe did not come first, they gave him the second position, with Lyonga Ekema Robert coming third and Thomas Tatah 4th.

Till this date, no male athlete has succeeded in the feat of winnining three races on the trot. Many athletes mostly from the North West region have come close but failed at the doorstep of glory. Shey Joseph Kongnyuy won in 1999 and 2000, was beaten in 2001 by Dominic Tedjiozem, just for Kongnyuy to win again in 2002. He has three wins therefore but never in a row. Charles Ngonga ponga won in 2003 and 2004, but was beaten in 2005 once again by Dominic Tedjiozem, the mathematics teacher from Bafoussam who became the dream killer of the race. The 2006 and 2007 editions were won by Januarius Bonkiyung but when he came for the crown in 2008, he failed , outpaced by Charles Ngonga ponga who grabbed his third win but not successive. Gabsibuim Godlove met with same consequences in his run for a third win in 2014, when the trophy was lifted by Mbacha Eric.

The excitement therefore fast left the men’s competition to embrace the women who first competed on the slopes in 1983. The first to win three editions was Mojoko Ngonja Emilia in 1983, 1985 and 1986. Her first stumbling block was Ewelisane Sarah Njie in 1984, and when she won two editions in a row in 1985 and 1986, the 1987 race failed to go her way, relegated to second place by a stronger and more robust Christiana Embelle Etonge. That was before a series of foreign wins, three in a row by Helene Diamentedes from England in 1988, Rueda Fabiola from Argentina in 1989 and Sally Goldsmith from England in 1990.

After which the winning machine and mountain lioness took over the command baton. Sarah Liengu Etonge won three successive editions and won the Queen of the mountain crown, with a record 7 wins by the end of her career.

With other race animators like Ngwang Catherine, Yvonne Ngwaya and Ngalim Lizette winning similar feats, their decline left a big gap to fill as the sporadic winners today take turns, thereby relegating the crown to the background, a rough push that covers the rays of a one time race objective, the main reason for the excitement.

Today, the objective remains the cash prize, 10 million cfa francs for the winners in both categories, the only motivating factor for the present generation. With the evolution of objectives came that of ideas and expectations, though the excitement remains especially with the growing local population who still see the event as theirs, setting family agendas around the major event, as they sit around the fire to recount the stories of past editions, those editions that were void of personal gains, those editions when athletes represented their people and community, the grand final being the 1988 edition when they last tasted victory. How to bring back those memories with a fresh victory for now seems a far-fetched dream.

By Simon Lyonga la Molombe